Burgundy Heritage

Burgundy eyes were smiling on 4th July last year when, after nine years of campaigning, it was announced that the region had been successful in its bid to be recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site. A few days later a grand celebration was held in the grounds of the Château de Meursault. It started as an early evening picnic, but as the sun set behind the château it segued into a full-blown party with live music and fireworks. Estimates of attendance ranged from 1,500 to 2,000. The message is clear: Burgundy is on a roll. After decades in the doldrums in the midtwentieth century, things finally began to come good about 30 years ago and they have barely looked back since. Read on to enjoy an armchair tour of Burgundy, and if that sparks your interest, then take the next step and go visit.

Major Grapes

Chardonnay for white and Pinot Noir for red are the two great building blocks of Burgundy. Chardonnay is a relatively easy grape to grow and vinify, hence its ubiquity around the globe. There are plenty of pretenders to white Burgundy’s crown from the likes of California, South Africa and Australia. At their best, however, the ‘holy trinity’ of Chassagne-Montrachet, Puligny-Montrachet and Meursault still reign supreme. Pinot Noir is a trickier customer, a celebrated diva that needs careful handling and mollycoddling if the best is to be got out of it. When that happens and it sings pure and true, there is no greater expression of the winemaker’s craft on the planet.

Minor Grapes

Aligoté for white and Gamay for red. To turn your nose up at Aligoté was once de rigueur but is now very last century. In the best hands, it produces wines of flinty-sharp precision with impressive intensity of flavour. Gamay is better known than Aligoté, mainly thanks to its use in Beaujolais, but it’s also found in Bourgogne Passetoutgrains, where it’s blended with Pinot Noir to yield wines of juicy succulence.

A Drop of History

Today’s map of Burgundy owes much to the efforts of the Cistercian and Benedictine monks, who over the course of centuries drew up the detailed vineyard boundaries that have remained largely unchanged ever since. Their power and influence, and that of the aristocracy, was shattered by the French Revolution, which heralded a bewildering fragmentation of vineyard ownership. This continues today, with tiny slivers and patches of vineyard constantly changing hands, though the latest trend sees multinational drinks companies and vastly wealthy individuals swooping in to buy whole domaines. Perhaps they are the church and aristocracy of today?

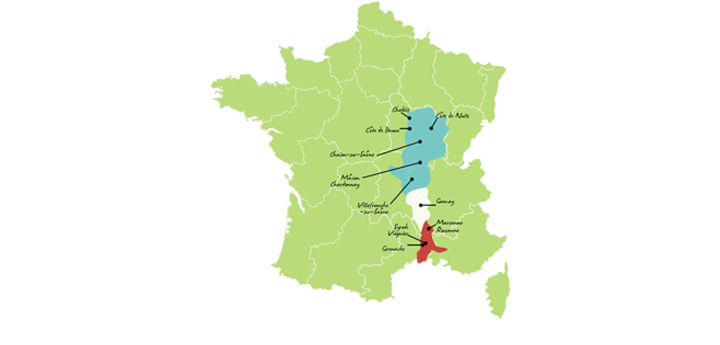

Côte d'Or

The ‘Golden Slope’ is the heart of Burgundy, the fillet in the steak as it were. It’s the most fabled strip of vineyard on the planet. Tiny plots of land in the most exalted vineyards change hands for prices equivalent to tens of millions of euro per hectare. The Côte divides neatly north and south into, respectively, the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune. Roughly speaking, the greatest reds come from the north and the greatest whites from the south, but in Burgundy, more than anywhere else, beware generalisations. Names to look out for include Gevrey-Chambertin, Chambolle-Musigny and Vosne-Romanée for red wines. For white, look for the ‘holy trinity’ mentioned above and watch out for Saint-Aubin coming up on the outside.

Beaujolais

Poor Beaujolais. It’s one of the best-known wines in the world, yet it’s derided and misunderstood, and it’s all Beaujolais’s own fault. Beaujolais Nouveau may have raised the image of the wine, but it also destroyed its reputation and saw it pigeon-holed as a wine of little style and no substance. Which is a shame, for the real thing is one of the most immediately likeable wines in the world, full of mouthwatering fruit and juicy acidity. One sip of the Fleurie tasted here should be enough to convince all but the most curmudgeonly doubting Thomas.

Chablis

Burgundy’s northern outpost is only a quick gallop down the A6 from Paris, yet it’s a world apart, a vineyard region whose wines can truly claim to be unique. Here, the Chardonnay grape gives wines of steel and savour, lean and precise expressions largely unadorned by oak ageing. They are sonatas to the Côte d’Or’s symphonies, but they are no less impressive for that. In a world dazzled by sumptuous, mouth-filling flavours, they stand as beacons of restraint.

Mâconnais

Aside from Chablis, Mâcon-Lugny is probably the best-known Burgundy in Ireland. Again, the region takes its name from a town, Mâcon, that lies about 55 kilometres south of Chalonsur-Saône. Only a small amount of red wine is produced here. Chardonnay is king and reaches its apogee in Pouilly-Fuissé, which lies right at the southern end of the region. Here, on the slopes surrounding the Roche de Solutré, a spectacular natural outcrop, it sometimes reaches levels of quality that can challenge the whites of the Côte d’Or without the knee-trembling prices.

Côte Chalonnaise

The words ‘value’ and ‘Burgundy’ don’t always sit comfortably in the same sentence, but it is in the Côte Chalonnaise, which takes its name from the town of Chalon-sur-Saône, that the two can co-exist without conflict. It is probably in this region that standards have improved most in recent years and now the future looks bright for wines such as Rully, Mercurey, Givry and Montagny. Also keep an eye out for the aptly named Bouzeron, where Aligoté takes pride of place ahead of Chardonnay.